Party Team Extreme

This post isn’t for the faint of heart–or liver.

I’ve been kicking this idea around for a while to make a list of the biggest/best/awesomest parties and festivals from all around the world, and systematically attending them. You’ll find the current list at the bottom of this post, and I encourage you to suggest others!

So what about the PARTY TEAM? Well, if you’re the jet-setting, adventure-seeking, pretty-bitchin-awesome type of person, I invite you to come along for this rad journey. You don’t have to come for all of the events, but I’d love to assemble a crew who can descend on any festival whether it’s Mardi Gras, Carnival, or La Tomatina and GO HARD. Like I said before: DO YOU HAVE WHAT IT TAKES?

If you’re reading this, you just might…

If you want to learn more, the list of events is below. I’m arranging them in a rough order of how I’m thinking of attending them, starting with US/Canada events and moving farther abroad. Anything past the first two or three is not in any sort of order other than how soon I found them. Continue reading “Party Team Extreme”

Reblogs for 20101030

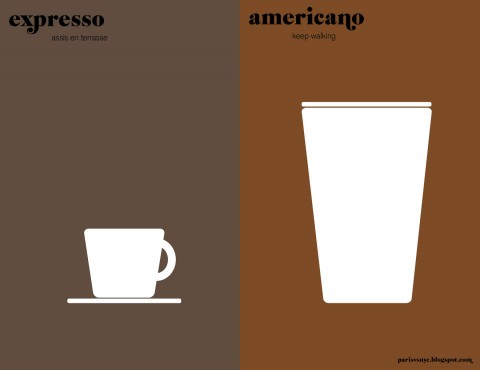

- Paris versus New York

Paris versus New York is a friendly visual match between those two cities, as seen by a Parisian-based-and-lover on New York : details, cliches and contradictions. Absolutely fantastic.

(thank you Jolayne)

Reblogs for 20101030

Reblogs for 20101022

- thedailywhat:

Unusual Jewelry of the Day: “’Til Death Do Us…

Unusual Jewelry of the Day: “’Til Death Do Us Part” engagement ring knuckle duster by Kate Bauman.

4” x 3”. Sterling silver, cubic zirconia. 2006.

[buzzfeed.]

- Photo

Reblogs for 20101018

Reblogs for 20101005

Reblogs for 20101004

- Photo

- Photo

- Collective intelligence in small teams

A new study co-authored by MIT researchers documents the existence of collective intelligence among groups of people who cooperate well, showing that such intelligence extends beyond the cognitive abilities of the groups’ individual members, and that the tendency to cooperate effectively is linked to the number of women in a group.

Many social scientists have long contended that the ability of individuals to fare well on diverse cognitive tasks demonstrates the existence of a measurable level of intelligence in each person. In a study published Thursday, Sept. 30, in the advance online issue of the journal Science, the researchers applied a similar principle to small teams of people. They discovered that groups featuring the right kind of internal dynamics perform well on a wide range of assignments, a finding with potential applications for businesses and other organizations.

“We did not know if groups would show a general cognitive ability across tasks,” said Thomas W. Malone, the Patrick J. McGovern Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management, one of the authors of the paper. “But we found that there is a general effectiveness, a group collective intelligence, which predicts a group’s performance in a lot of situations.”

That effectiveness, the researchers believe, stems from how well the group works together. Groups whose members had higher levels of “social sensitivity” — the willingness of the group to let all its members take turns and apply their skills to a given challenge — were more collectively intelligent. “Social sensitivity has to do with how well group members perceive each other’s emotions,” said Malone. “In groups where one person dominated, the group was less intelligent than in groups where the conversational turns were more evenly distributed.” Teams containing more women demonstrated greater social sensitivity and in turn collective intelligence, compared to teams containing fewer women.

When ‘groupthink’ is good

To arrive at their conclusions, the researchers conducted two studies in which 699 people were placed in groups of two to five and worked on tasks that ranged from visual puzzles to negotiations, brainstorming, games and complex rule-based design assignments. The researchers concluded that a group’s collective intelligence accounted for about 30 to 40 percent of the variation in performance.

Moreover, the researchers found that the performances of groups were not primarily due to the individual abilities of the group members. To determine this, many of the participants also performed similar tasks individually. The average and maximum intelligence of individuals did not significantly predict the performance of their groups.

The paper’s lead author was Anita Woolley, an assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business. The other researchers in the study were Christopher Chabris, an assistant professor of psychology at Union College in New York; Malone; Alexander Pentland, the Toshiba Professor of Media Arts & Science at the MIT Media Lab; and Nada Hashmi, a doctoral candidate at MIT Sloan. The study received funding from the National Science Foundation, the Army Research Office and Cisco Systems.

To record the interactions of people, the researchers equipped study participants with wearable electronic badges — designed by Pentland’s Media Lab group — that provided a complete record of a group’s conversational patterns and revealed a group’s propensity to take turns. “When you do that, it’s possible to get patterns you’ve never seen before,” said Pentland.

Only when analyzing the data did the co-authors suspect that the number of women in a group had significant predictive power. “We didn’t design this study to focus on the gender effect,” Malone said. “That was a surprise to us.” One implication is that the level of collective intelligence should keep rising along with the proportion of women in a group. To be sure, as Malone said, that gender effect is a generalization. “Of course some males have more social skill or social sensitivity than females,” Malone acknowledged. “What our results indicate is that people with social skills are good for a group — whether they are male or female.”

Malone said he believes the study applies to many kinds of organizations. “Imagine if you could give a one-hour test to a top management team that would allow you to predict how flexibly that group of people would respond to a wide range of problems that might arise,” he said. “That would be a pretty interesting application. We also think it’s possible to improve the intelligence of a group, by either changing the members of a group, or teaching them better ways of interacting.”

How universal is it?

Colleagues in the field found the results intriguing. Jeremy Gray, an associate professor of psychology at Yale University, said the study “was very well done,” adding that “the key point is great, that features of the group can be more important than features of the individuals that make up the group, for determining outcomes.”

However, Gray, responding to questions by e-mail, noted that the study raises additional questions for further investigation. Beyond the relatively routine tasks used in the study, he wrote, “high-stakes or high-risk situations would also be very important to understand. There is no guarantee that the same pattern of results would hold, for example, for a jury deliberating a death-penalty case, a corporate board facing a hostile-takeover bid, criminal gangs battling a rival gang, and so on. We just don’t know yet.” Moreover, he added, “clarifying the conditions under which the proportion of women makes a difference would be interesting.”

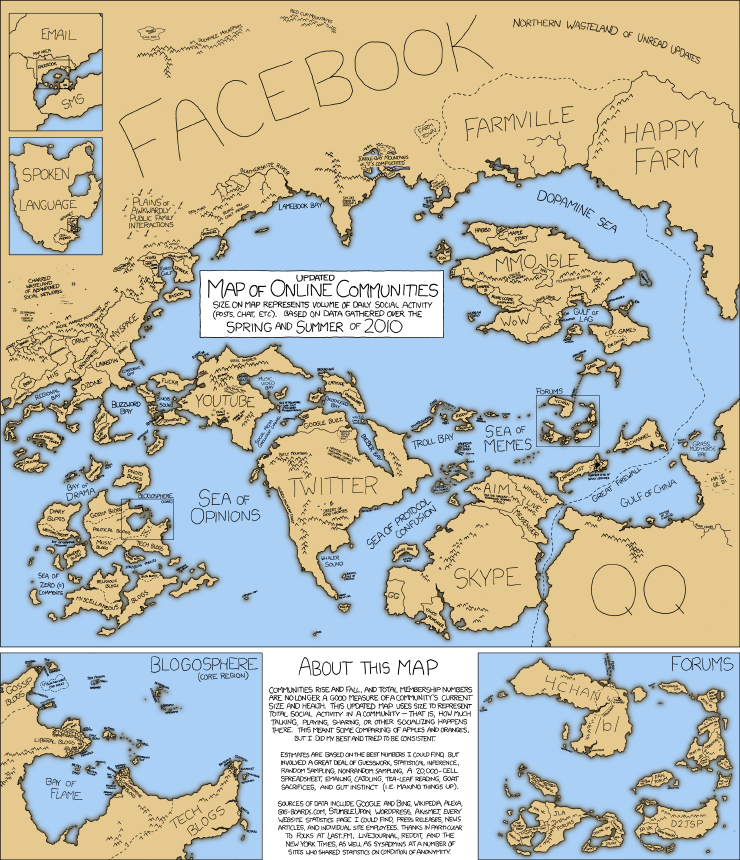

Malone said the co-authors “definitely intend to continue research on this topic,” including studies on the ways groups interact online, and are “considering further studies on the gender question.” He added that “collective stupidity,” the failure of a group to perform to the abilities of its members, exists along with collective intelligence. “Part of the research agenda for this field is to understand better the conditions that lead to one rather than the other,” Malone explained. “Many factors can affect a group’s intelligence, including the social sensitivity, norms, and motivations of group members, as well as the composition of the group.” For now, Malone said his group has identified a general principle indicating how the whole really can be greater than the sum of the parts.

“Having a bunch of smart people in a group doesn’t necessarily make the group smart,” concluded Malone.

Reblogs for 20100928

Reblogs for 20100926

- 2010_06_11_15_57_www_yapfiles_ru_files_100814_dlya_shizo.gif (GIF Image, 400×248 pixels)

- The Troubles With Modern Sleep: Myths, Memory, and Mortality

Are you getting eight hours of uninterrupted sleep every night? …Why? Though many of us consider the 8 hour (really, 7 to 9 hour) period of sleep as the ultimate way to rest, our bodies may be set up differently than we think. Natural sleep cycles tend to occur in several parts, change with the seasons, and take place partially in the day. Some people actively look to improve their sleeping habits by switching to several evenly spaced naps in a 24 hour period. Science may provide a way to get by on less sleep thanks to genetic engineering. Research at the UC San Francisco has identified a genetic mutation that allows humans, and genetically altered mice given the gene, to sleep less than their peers and still be awake and well rested. No matter how you look at it, our notions of when to sleep, how long to sleep, and why we sleep may need to be updated as we move into the future. Down a few caffeine pills, drink some warm milk, and crank up the volume on the white noise – it’s time to re-examine our confusing and conflicting ideas about sleep.

Our first main problem is that people have largely strayed from ‘natural sleep’. For the majority of living creatures on Earth, sleep is intimately connected to the Sun. Humans have tried to be an exception. The advent of widespread artificial light in the 19th century allowed us to start staying up later. In the 21st century the majority of people in industrialized countries have shifted their waking time so that it no longer directly corresponds to sunlight hours. That flexibility is what allows us to travel internationally, work in rotating shifts, and get things done. However, it could also be stunting our creativity, hurting our memory, maybe even sapping our intelligence. Here’s Jessa Gamble, a science journalist in Canada, raising her concerns about our departure from natural sleep during her presentation at TED this year:Gamble’s talk is woefully short on scientific citations (her upcoming book on the subject is likely more thorough), but I can fill in some of the gaps. First, her assertion that people naturally sleep in two segments at night (known as segmented sleep) is well supported by a landmark paper by Thomas Wehr published in the Journal of Sleep Research. Back in 1992, while at the National Institute of Mental Health, Wehr demonstrated that people put into winter-like periods of sunlight (<10 hours) would develop a biphasic sleep. Essentially they slept, woke up, and slept again. During that intermediate waking period, the body produced larger amounts of the hormone prolactin (Gamble mentions this). Prolactin is reponsible for lactation in mammals, but it has also been linked to happiness, sexual gratification, and relaxation. What’s so important about prolactin? Well it’s one of the necessary hormones for our functioning, it counters dopamine, and it might help you stay smart. Research in the journal Science and the Journal of Neuroscience show that it helps increase mental plasticity in women during pregnancy. It may be doing the same in everyone.

‘Natural sleep’ is probably not eight hours of uninterrupted sleep. In fact, a little interruption is probably good, at least in longer winter nights. Humans in short summer nights (in Wehr’s experiments) generally didn’t experience biphasic sleep. But many people will tell you the importance of getting a nap during the day, especially during the hot summer. Research in Germany has shown that even a relatively short nap (20 mintues or so) can have a pronounced effect on memory. The siesta is good for you.

So, during some times of the year your body is probably adapted to sleeping longer each night with a break in the middle. And during all or part of the year your body probably wants a nap during the day. Returning to this ‘natural sleep’ cycle seemingly has mental benefits, and those that follow such cycles may be better able to remember important information, and stay alert.

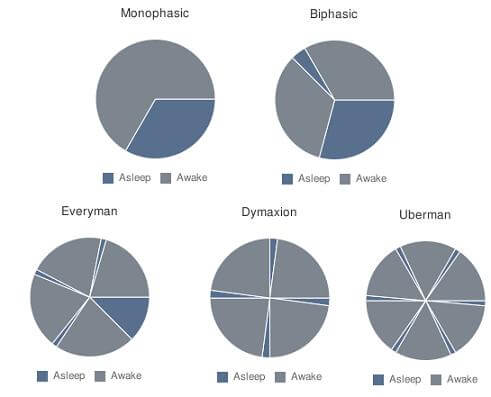

In an effort to capitalize on the segmented sleep phenomenon and to capture more awake hours during the day, some people have attempted to switch their clocks completely. They look to sleep a shorter amount of time per day (sometimes as little as two hours) and to do so in smaller chunks. This polyphasic approach to sleep has waxed and waned in popularity. YouTube and the internet at large are ripe with examples of people attempting, and generally failing, to switch to a new cycle. I don’t really want to get embroiled in the controversy about whether such sleep cycles are feasible, so I’ll pass the buck: here’s a pro-polyphasic site, and here’s one of the more popular counter arguments (with update). The following video features one of the more discussed researchers, Claudio Stampi, exploring polyphasic sleep in a semi-lab setting (make sure to watch till the end):

Many of those wishing to switch to a polyphasic sleep schedule do so because they already have trouble with getting a good night’s rest. Insomnia affects around 64 million people in the US, and many more around the world. While the causes of insomnia, and sleep deprivation in general, vary from case to case, the end results are almost universally unpleasant. Increased depression, lack of concentration, and feeling of stress are common complaints. Death may need to be added. A recent study published in the journal Sleep demonstrated that men who experience insomnia for more than a year had an increased incidence of mortality. In other words, although severe lack of sleep can’t kill you directly, it lessens your chance for a long and healthy life.

Examples of various forms of sleep. Theoretical polyphasic patterns are listed in the second row. Gamble's example of 'segmented sleep' would be closest to Biphasic sleep, except with a period of wakefulness inside the larger sleep segment.

I should point out, however, that some scientists feel that resting, not sleep itself is the necessary ingredient for survival. Researchers at the University of Wisonsin are exploring the possibility that falling asleep can be completely avoided. They point to numerous animals that challenge our ideas about the necessity of becoming unconscious.

Our modern world values productivity so much that people are willing to pursue longer waking hours, even though we generally know that a lack of sleep is both unpleasant and dangerous. In the future, we may all be able to stay awake without any of the dangers. Ying-Hui Fu and colleagues at UCSF have found that a mutation in the DEC2 gene can help some humans function better than their peers with less sleep. Transplanting that gene into mice allowed them to do the same. While the genotype for getting by on less sleep is certainly more complex than a single gene, Fu’s work suggests that we may one day augment ourselves beyond the need for 8 hours of slumber.

That day is a long way off, and in the meantime I think we’re going to continue to do silly, and probably even dangerous things, to avoid getting natural sleep based on sunlight patterns. We live in a world of 5 hour energy and late night television. We have grown accustomed to staying up to whatever time we want and sleeping as little or as much as we like. Most of us probably feel pressured to do more in each day, and our sleeping habits suffer.

When we examined longevity we discussed how a few simple lifestyle choices (eating healthy, getting regular exercise and avoiding stress) seemed to be the secret to living longer and healthier lives. For many of us, switching our diets and activities to mimic that example seems feasible. But what if we also need to go to sleep and rise with the sun? Could we do so? Would we even want to?

My guess is no. Even if natural biphasic sleep with a mid-day nap is probably the healthiest, I doubt many of us will pursue such a schedule. There’s simply too much going on, too much pressure to work and play for us to sacrifice our flexibility. As our digital lives become more important we may face increasing pressure to stay connected for longer portions of the day, even though we know that unplugging is good for our health. The future may be filled with people striving to stay awake as much as possible. Genetics and other technologies could give us a means to do just that. Either way, it’s pretty obvious we’re going to try.

[image credits: Wikicommons]

[sources: Shingo et al Science 2003, Lahl et al JSR 2008, Wehr JSR 2008, Gregg et al JNS 2007, Vgontzas et al Sleep, 2010, He et al Science 2009, Cirelli et al PLOS 2008]Related Posts:

- Zeo Headband Monitors, Analyzes Your Brain While You Sleep (Video)

- Chip for Eye Implants Could Run for a Year on Millimeter Sized Battery

- Blue Zones – Places In the World Where People Live to 100 and Stay Healthy

- Blue Zones – Places In the World Where People Live to 100 and Remain Healthy

- Body 2.0 Here We Come: Fitbit Tracks Your Vital Signs 24/7

- Chan.gif (GIF Image, 304×240 pixels)